To understand the desperation Apple felt in the mid-to-late 1990s, look no further than to one particular t-shirt. On the front was a 3-D rendered numeral eight. On the back, the words “Hands-On Experience” and Mac OS 8 logo.

At Apple’s Worldwide Developer Conference in June 1996, many of us got to experience the future of the Mac for the first time. We got the t-shirt for test driving Apple’s transformational new operating system, one that replaced the woefully out-of-date classic Mac OS with something that could compete with Microsoft. The operating system was nicknamed Copland and it never shipped. The “Hands-On Experience” shirts and an accompanying book, “Mac OS 8 Revealed,” were as good it was ever going to get.

With its back against the wall and its internal software development failing, Apple was left with only desperation moves. Fortunately, it made a good one, resulting in Mac OS X 10.0, which shipped 20 years ago this week.

Classic Mac OS had to die

Classic Mac OS—the Mac operating system before OS X—was built on a shaky foundation. As revolutionary as the original Mac was, it was also an early-1980s project that didn’t offer all sorts of features that would become commonplace by the late 1990s.

That operating system had been originally designed to fit in a small memory footprint and run one app at a time. Its multitasking system was problematic; clicking on an item in the menu bar and holding down the mouse button would effectively stop the entire computer from working. Its memory management system was primitive. Apple needed to make something new, a faster and more stable system that could keep up with Microsoft, which was coming at Apple with the user-interface improvements of Windows 95 and the modern-OS underpinnings of Windows NT.

That’s where the t-shirt came in. Copland was intended to be Mac OS 8, and it was supposed to ship in the middle of 1996. It was going to offer pre-emptive multitasking, protected memory, a redesigned user interface with multiple themes, intelligent search, broad support for OpenDoc (if you don’t know, don’t ask), and much more. The ship date slipped to the middle of 1997, and some of Copland’s more ambitious features were pushed off even further to a theoretical OS 9 code-named Gershwin. And then, a few months after Apple handed out those t-shirts, it killed the entire project.

What instead shipped as Mac OS 8 in the summer of 1997 was a version of the classic Mac OS, dressed up in the clothes of Copland. The advanced search technology, redesigned filesystem, revamped multitasking, and memory protection were nowhere to be found. While it offered some improvements over System 7, Mac OS 8 did nothing to solve Apple’s larger operating-system problem.

In a spectacularly humbling moment for Apple, the company began searching for a company from which it could buy or license an operating system or, at the least, use as the foundation of a new version of Mac OS. The company’s management, led by CEO Gil Amelio and CTO Ellen Hancock, clearly had come to the conclusion that Apple itself was incapable of building the next-generation Mac OS.

Though there were a lot of wild ideas thrown around (building Mac OS atop Microsoft’s Windows NT kernel and rebuilding the platform using Java were two of them), the two most obvious targets were small companies with operating systems that had the modern features Apple wanted most. Both were, perhaps unsurprisingly, being run by former Apple executives.

In one corner was Be, Inc., run by Jean-Louis Gasseé. Be was developing a new, modern graphical interface from scratch, and it ran on the same PowerPC chips Apple used at the time. You could even reboot from Mac OS into BeOS on certain Power Mac models. BeOS was gorgeous, fast, and offered advanced search capabilities that were far ahead of its time. Its biggest liability was that it was unfinished, so if Apple were to buy it, there would be a huge amount of development ahead of it.

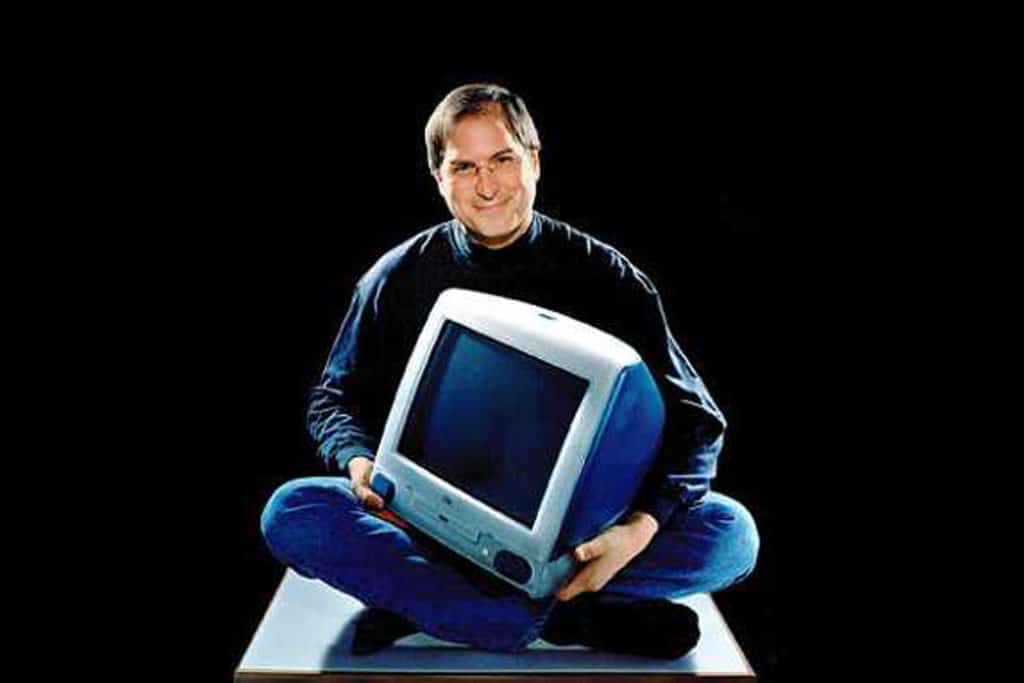

The NeXT deal not only gave Apple a modern Mac operating system, it brought Steve Jobs back to Apple.

Time

In the other corner was NeXT, founded by Steve Jobs. Although perhaps a bit less cutting-edge than BeOS, NextStep was a more complete package, and it also had the Steve Jobs factor. Amelio and Hancock were apparently convinced, and brokered a $400 million deal to buy NeXT and bring Jobs back to Apple in an advisory role.

You know what eventually happened to Jobs. He was an “advisor” who became a board member who became the interim CEO who ultimately transformed Apple into one of the world’s biggest and most regarded companies by the time of his death in 2011.

What you might not know is that NextStep, that operating system that came over in the deal, was essentially the core of Mac OS X. The software decisions made at NeXT in the 1990s reverberate to this day, in code that runs not just on the Mac, but on all of Apple’s devices—iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, and Apple TV.

The long road to OS X

Apple bought NeXT in December of 1996. Mac OS X 10.0 shipped in March of 2001. As powerful and sophisticated as NextStep was, it took the new Apple software organization—led by NeXT’s Avie Tevanian—more than four years from acquisition to a “completed” version of Mac OS X. (And stopping the clock 20 years ago this week is probably unfair. I’d mark the end of the Mac OS X transition as April 2002, when Steve Jobs held a funeral for Mac OS 9 because OS X was finally good enough.)

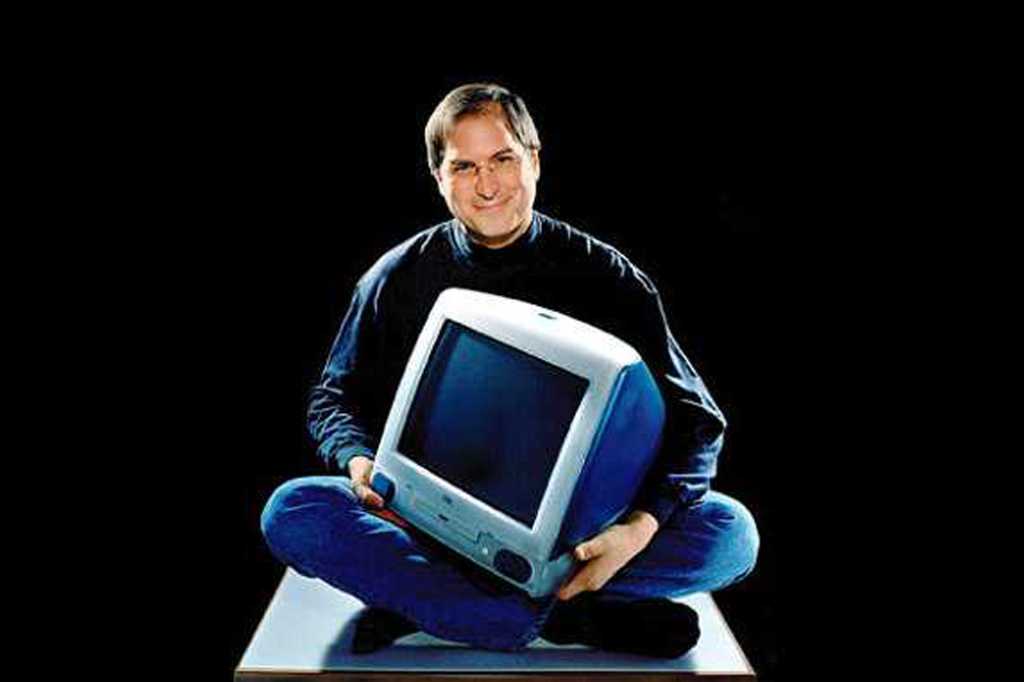

What took so long? The NeXT interface needed to be revamped to resemble Mac OS in order to get Mac users on board with the new operating system. This was an area where Mac OS really won the day. With each successive preview release, NeXT’s influence faded away. Perhaps its greatest interface legacy on macOS today is the Dock, which never existed before OS X.

NeXT’s greatest legacy is on every Mac today: the Dock.

Apple

There were also several false starts, including Rhapsody and Mac OS X Server, weird hybrids of NextStep and Mac OS that didn’t get it right. Apple realized that it couldn’t just ship NeXT’s app-development environment, the Yellow Box–the ancestor of present-day Apple’s Cocoa–and expect the developers of all Mac apps to completely rewrite their software for a new platform.

Instead, Apple had to create a layer cake of an operating system, with Yellow Box (which allowed NextStep developers such as The Omni Group to become fledgling Mac developers) living alongside Blue Box, a modernized version of the existing Mac OS application environment. By creating Carbon, a set of modernized Mac-style interfaces, Mac developers could modify their existing apps to run on Mac OS X, rather than needing to rewrite them.

And of course, there was Classic, a virtualized version of the original Mac OS that would be capable of running unmodified apps. Using Classic was a supremely weird experience, but it did provide a bridge for people who couldn’t give up their old software.

This is one big reason why Mac OS X took as long as it did to make it out into the world. It needed to update the NeXT app approach (which survives to this day across Apple’s platforms) while building multiple layers of compatibility to give Mac software a place to run. And until Microsoft and Adobe publicly committed to building OS X native versions of their apps, it was an open question if Apple could pull it off.

More than Steve Jobs

It’s often said that Steve Jobs was the most valuable asset in the Apple-NeXT deal. And it’s impossible to argue that, given what happened to Apple in the several years after the deal.

But it’s also an unfair to point to make. Apple’s entire operating-system strategy for the last 20 years has used NextStep as a foundation. Every iPhone app developer who uses classes such as NSObject, NSString, and NSArray are staring it right in the face: the NS prefix comes from NextStep.

So when we celebrate the 20th anniversary of Mac OS X, it’s important to realize what we’re celebrating. We’re celebrating a software release that was the culmination of Steve Jobs’s return to Apple. We’re celebrating the operating system we still use, two decades later. But we’re also celebrating the foundation of iOS, iPadOS, tvOS, and watchOS.

In that way, this isn’t just the 20th anniversary of Mac OS X 10.0. It’s the 20th anniversary of modern Apple, and the end of the dark days when Apple couldn’t fix its own operating system. (Been there, saw that, got the t-shirt.)

Note: When you purchase something after clicking links in our articles, we may earn a small commission. Read our affiliate link policy for more details.