When Apple’s latest operating systems debut this fall, many of their users will benefit from a whole new kind of built-in privacy protection in the form of iCloud Private Relay.

While your actual web traffic has long been generally secured by encryption using HTTPS connections (that little padlock we all got used to looking for in the address bar), there have remained ways in which your ISP or the website you’re visiting could learn more about your traffic and perhaps even use that information to build a profile of you.

iCloud Private Relay, which will be available to anyone paying for an iCloud storage plan, aims to protect against two of these loopholes. The first is when your ISP can tell what site you’re visiting: for example, that you entered or clicked on a link to apple.com. While it can’t necessarily tell what pages or content you accessed, it does often know the top-level domain because that has to be translated into an IP address using the Domain Name System (DNS). Combine with all the domains that you visit on a regular basis, that could allow your ISP to build a profile of you that advertisers might be interested in.

The other loophole is that the website you’re contacting knows some information about you, because it can see your IP address. For one thing, that allows the server to trace that IP address back to a specific geolocation. (Precision varies, but usually at least your city, if not even more specific—when I geolocated my IP, it gave me a location about half a mile from my house.) But it can then cross-reference that IP address with other sites, companies, advertisers, etc. in order to build a richer profile about you.

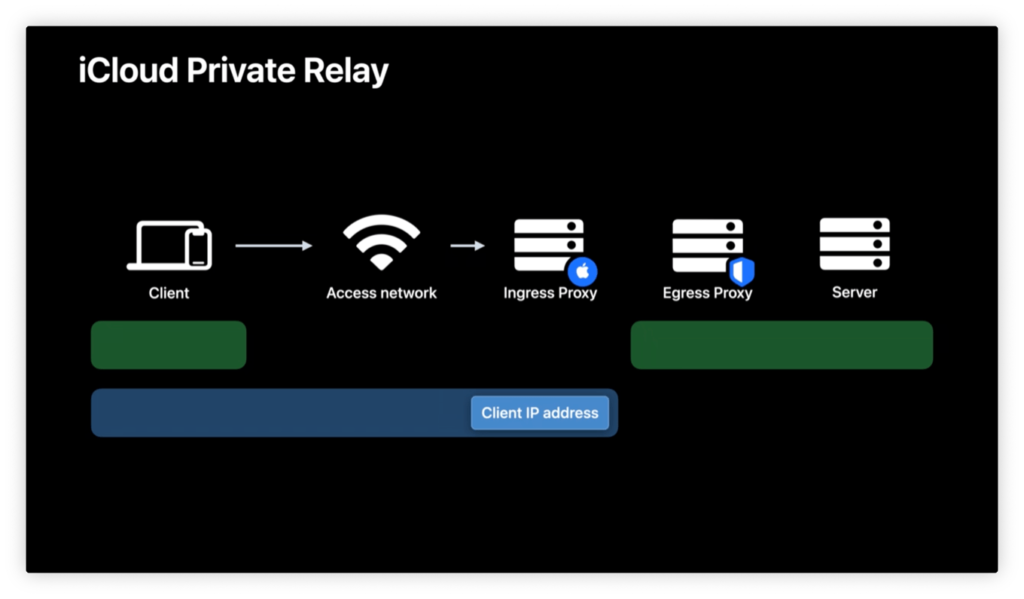

iCloud Private Relay helps combat both of these loopholes through the use of a dual-hop architecture. Essentially, any traffic from Safari on an Apple device, as well as DNS queries, and a subset of app traffic (specifically insecure web traffic), will be routed through two separate servers: an ingress proxy managed by Apple that hides your IP address (by essentially slapping its own IP address on the request), and an egress proxy, run by “a content provider,” which only sees the server you’re trying to access.

This means that your traffic still goes to the website in question, but it gets only the ingress server’s IP address. There are several ingress proxies which bundle together users from specific regions, providing broad geolocation powers. (So, for example, the server might know you’re from North America, or even from the northeast—Apple says a list will be provided, though I wasn’t able to locate the document at the time of this writing.) Apple urges websites to stop using IP addresses for identity, relying instead on having users login or by explicitly asking for location information only when really needed.

While iCloud Private Relay will affect the bulk of web traffic from the devices of iCloud+ users, it does not apply to traffic over the local network or via private domains, transmitted via VPNs, or using proxy servers.

Most apps won’t have to make significant (or, in many cases, any) changes to use iCloud Private Relay, as long as they’re using modern APIs for network access—the system comes baked in.

One area that might run into challenges, however, are content filter and parental control services that aren’t run on a device. But apps that use use the Screen Time API will still be able to see and filter websites before those sites can be accessed. (Given that local network traffic is exempt, filtering at a local network level seems like it would continue to work, but it’s not entirely clear.)

For institutions that have policies requiring monitoring or intercepting traffic on a entire network (such as enterprise or education), blocking the hostname of the iCloud Private Relay ingress proxy will effectively disable iCloud Private Relay. Users who join that network will be notified and prompted to continue using the network without iCloud Private Relay, or not using the network.

All in all, iCloud Private Relay is poised to be one of those services that’s essentially transparent to users but has significant benefits in terms of decreasing tracking. It obviously won’t solve all privacy concerns: at the end of the day, if you’re logging into a website and have already given them your personal details, they can still build a profile on you and your activities on their site. But it may make it harder for that information to be collected without your knowledge or combined with details from other sites.

[Dan Moren is the East Coast Bureau Chief of Six Colors. You can find him on Twitter at @dmoren or reach him by email at dan@sixcolors.com. His latest novel, The Aleph Extraction, is out now and available in fine book stores everywhere, so be sure to pick up a copy.]

If you appreciate articles like this one, support us by becoming a Six Colors subscriber. Subscribers get access to an exclusive podcast, members-only stories, and a special community.