Apple is not a person. It’s easy to forget sometimes, but Apple is not Tim Cook or the imprint of Steve Jobs or Phil Schiller or any other person. It’s an entity made up of thousands of people and a corporate culture (which, I’ll grant you, was largely defined by Jobs) that evolved over time.

That said, Apple does have a corporate personality all its own, and I’ve been thinking lately about one of its stronger traits: pride. No company wants to admit failure in its press conferences and PR blitzes—those utterances are best said late on a Friday afternoon in a terse statement to a sympathetic media outlet.

But Apple is in another league. Failed features don’t disappear—they’re replaced by exciting new features. One of its most colossal flops, the Power Mac G4 Cube, was famously put “on ice” rather than retired, in a press release that fantasized that it might eventually return. The mistake of the 2013 Mac Pro was only admitted to as part of a handpicked media roundtable where it was put in the larger context of a recommitment to professional Mac users.

Considering that pride, what happens when the company decides that many of the decisions it made a few years earlier were mistakes, actually? What does it look like when Apple makes a strategic retreat?

It feels like we’re about to find out.

When it’s not a retreat

Now, some walk-backs aren’t walk-backs at all. Apple says a lot of things that are meant as distractions, either because the company doesn’t want to steal its own thunder about a forthcoming product, or because it just hasn’t decided how it wants to approach a category.

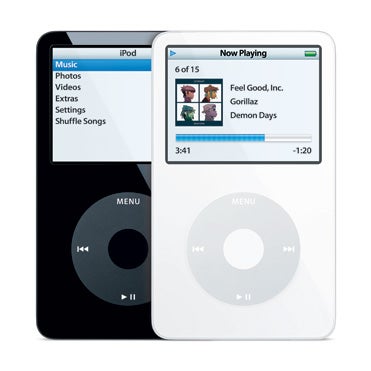

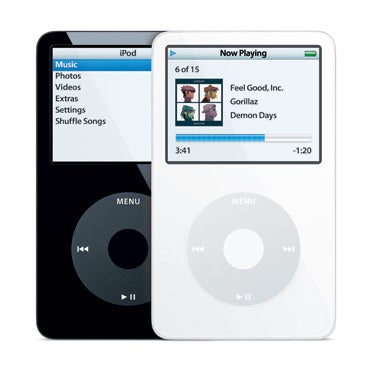

Most famous among these sorts of distractions is Steve Jobs famously saying that nobody would want to watch video on an iPod. Not only did that statement downplay Apple’s failure to deliver a video iPod, it also hid the fact that Apple was working hard to deliver that iPod soon after. This is a classic page out of the Jobs playbook: downplay features you don’t have, and when you finally offer them, declare that all similar features weren’t good enough—but that you’ve gotten it right.

Lots of people have gotten into trouble assuming that such statements were Apple doctrine. Jobs famously mocked styluses on touch devices—his statement, which was always meant to criticize devices that relied on styluses as their primary input method, was taken to signify that Apple would never make a stylus. The Apple Pencil eventually arrived, of course.

I’d argue that Apple’s insistence on the Mac not having a touchscreen is probably a similar sort of smokescreen. Of course, Apple currently combines a touchscreen with a keyboard and trackpad via the Magic Keyboard for iPad. It feels inevitable to me, but a Mac touchscreen is kind of like a wizard—it will arrive precisely when it means to. Expect it when it arrives, and not before.

Changing Apple’s mind

While Apple has a lot of pride, it also needs to listen to its customers—and it does, after a fashion. Jobs instilled in Apple’s culture an aversion to using focus groups and popular consensus as a way to design products; you’ve undoubtedly heard it compared to the idea that if Henry Ford had asked people what they wanted in terms of transportation improvements, they’d have asked for faster horses instead of cars.

But of course, Apple does do research, and scrutinizes its sales trends. And, yes, it is acutely aware of how it is being criticized, both in the mainstream media and in various tech-nerd circles that approximate portions of its audience.

If Apple was a person, we’d say that sometimes it changes its mind. I suspect that the truth is this: People inside Apple are always debating about what decisions to make, and feedback from the outside world can give more weight to those on the inside who lost the debate.

All the resistance in the world might have not succeeded in the creation of the buttonless iPod shuffle (probably because Steve Jobs loved it), but the reception it got made it crystal clear that it was the wrong decision, and Apple reverted to the previous design as if the buttonless model never existed.

Walking back the MacBook

So here we are in early 2021, with a strong possibility that Apple is about to undo most of the big changes it made to the MacBook. The Touch Bar is rumored to be a goner, MagSafe is reportedly returning, and Apple may be adding other I/O—HDMI? an SD card slot?—to the MacBook Pro as well.

On one level, it’s hard to believe this is true, specifically because Apple is so proud and it’s a bit embarrassing to revert to the general set of laptop features it offered half a decade ago.

And yet… hasn’t the avalanche already begun? (If so, it’s too late for the pebbles to vote.) We’ve already seen Apple remove the much-disliked (for both usability and reliability reasons) butterfly keyboard, across its entire line.

Perhaps it’s instructive to look back at what Apple did in late 2019, when it introduced the 16-inch MacBook Pro and rolled out the new keyboard design: “Featuring a new Magic Keyboard with a redesigned scissor mechanism and 1mm travel for a more satisfying key feel, the 16-inch MacBook Pro delivers the best typing experience ever in a Mac notebook.” Sounds like the playbook, doesn’t it? Let’s not even mention the old keyboard—the important thing is that the new keyboard is the best ever!

(This example also provides a key insight to how you revert to old features if you’re Apple—don’t. Instead, create something new that contains the old features, but with enough differences that you can call it something else and claim that it’s the best ever, not just the best since 2015.)

We listened to our customers

With that in mind, now imagine Apple rolling out a new MacBook Pro. If there’s a MagSafe connector on there, it obviously won’t be one of the old variety. Perhaps it’ll support full Thunderbolt connections, so you can magnetically connect to docks and monitors. It’ll be a new shape and size. And maybe it’ll even connect to a standard USB-C power brick, rather than being hard-wired into the brick as was the case with old MagSafe models.

Getting rid of the Touch Bar is the tough one. Will Apple just admit that its customers prefer physical function keys, or will it introduce some sort of new feature that it will sell as an advance in Mac input? (I’m just spinning this out of whole cloth, but imagine making the display a touchscreen and offering an on-screen version of the touch bar, perhaps combined with the Dock.) Apple would always prefer to make the story about its new invention, rather than the death of its old invention.

When you think about it, it’s kind of funny that Apple sometimes goes through these contortions. Personally, I don’t think it reflects badly on a company to just say, “We listened to our customers and found that they wanted an SD card slot and physical function keys.” Listening to your customers and giving them what they want is not the sign of a failure. It is, in fact, a sign of you doing the right thing. And if Apple were a person, I’d tell it that.

Note: When you purchase something after clicking links in our articles, we may earn a small commission. Read our affiliate link policy for more details.